Showing posts with label Music Box Theater. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Music Box Theater. Show all posts

Sunday, April 14, 2019

TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT (1944)

Chicago's Music Box Theater kicked off a new series today, I Wouldn't Stop Loving You: The Films of Bogie & Bacall, with a showing of the pair's first film, TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT. As it happens, a sudden snow storm pounded Chicago this morning, but it didn't stop a large and enthusiastic crowd from showing up to this first screening. It was a joyous experience, with the crowd laughing and applauding the movie, a recognition that few films have held up better than this one, one of cinema's true masterpieces. In coming weeks, the Music Box will show THE BIG SLEEP, DARK PASSAGE, and KEY LARGO. It's a short but impressive list. Of those films, I'd rank two A+ (TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT, THE BIG SLEEP), one A- (DARK PASSAGE), and one B+ (KEY LARGO). Some might quibble with here or there with my rankings, but I'm unlikely to encounter much resistance to the idea that these four films comprise one of the greatest of all movie star pairings.

I wrote about each of these four films back in 2014, after the death of Lauren Bacall. I'll link to my piece on TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT, a movie I've loved since I was a teenager, and that I treasure more every time I see it.

Monday, August 20, 2018

I WALK ALONE (1948)

Byron Haskin started out

in movies as a cinematographer and a special effects man—working his way up to

head of the Special Effects department

at Warner Brothers in the mid-forties—but when producer Hal B. Wallis

left Warner Brothers in the forties to start his own production company, Haskin

followed his old boss and started a directing career (or restart, I should say;

Haskin had made a handful of short films back in the silent days). His first

film post-Warner was I WALK ALONE. It should have led to much better things.

I WALK ALONE tells the

story of Frankie Madison (Burt Lancaster), a hood who has just been released

from jail after fourteen years. He’s back in town to look up his old partner,

Dink Turner (Kirk Douglas), a shifty bastard who has spent the last fourteen years

getting rich. Frankie wants his cut of the prosperity, and Dink is loathe to

give it to him. Caught between these two raging alpha males are mild-mannered

accountant, Dave (Wendell Corey), and sexy nightclub singer, Kay (Lizabeth

Scott).

The script is by Charles

Schnee, one of the best screenwriters of the era (THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL, THE

FURIES) from Theodore Reeves’ play “Beggars are Coming to Town”, and it is

unusually intelligent and perceptive. One of the interesting angles of the story

is the way Frankie finds that he is an anachronism in the new world of crime.

Dink is a businessman now, and Frankie’s two-fisted approach is hopelessly

outdated. When Frankie hires a bunch of thugs to help him storm into Dink’s

office and demand his cut, he discovers that Dink’s empire is really an amalgam

of three different corporations. The best Frankie can hope for is eight

percent—maybe, even that will depend on a vote by the stockholders.

Lancaster and Douglas, in

their first film together, are excellent. Both men are energetic,

hypermasculine performers, but what makes their pairing interesting is the

different effect each of them creates. Lancaster, even playing a goon, is an

honest, sympathetic protagonist. Douglas, on the other hand, is one of the

screen’s great bastards. His air of ruthless self-confidence is completely

mesmerizing, and somehow his self-satisfaction never gets in the way of his

appeal. Here these two actors already play together with the natural chemistry

that would sustain their repeated collaborations for decades to come.

Their support, both in

front of and behind the camera, is top rate. Wendell Corey, one of the most

dependable of supporting actors, finds a nice wounded dignity in his character,

and Lizabeth Scott, once again the morally questionable lounge singer (she must

have played this role a hundred times in the forties and fifties) is as sad and

beautiful as always. The film’s cinematographer is Leo Tover (who had just

photographed Scott in DEAD RECKONING the year before) and his work here is

evocative, classic noir photography. A sequence late in the film in which Corey

is chased down abandoned streets by one of Douglas’ thugs is just about

perfect.

If the film has a serious

flaw it is that it resolves its story a little too neatly at the end (a common

failing among films of the period, of course). Lancaster’s character takes a

swerve in the last few minutes that feels false. But this is a minor quibble

for a film firing on so many cylinders.

The following year,

Haskin would direct Scott in the noir masterpiece, TOO LATE FOR TEARS, followed

a few years later by an excellent John Payne picture called THE BOSS. While for

most of his career, he focused on adventure stories and science fiction, his

brief excursions into crime stories in the forties and fifties are enough to

make his name notable in the genre. After you see I WALK ALONE, and after you

see TOO LATE FOR TEARS and THE BOSS, you will find yourself wishing Haskin had

dabbled in crime pictures a little longer.

PS. I'd only seen this film on the small screen until the showing last night at NOIR CITY CHICAGO, the film noir festival (now in its tenth year!) put on by the Film Noir Foundation and Music Box Theater. If you love film noir, do yourself a favor and make your way to one of the annual NOIR CITY festivals in San Francisco, Chicago, Detroit, DC, and more.

Sunday, August 28, 2016

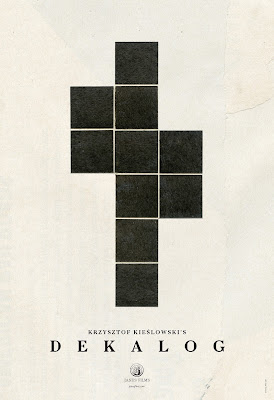

DEKALOG (1989)

Deep down, in my heart of hearts, Krzysztof Kieslowski might well be my favorite filmmaker. I can't think of a director whose work I find more beguiling, more entrancing, and, ultimately, more human.

I think his greatest accomplishment is the so-called Colors Trilogy: BLUE (1993), WHITE (1994), and RED (1994). BLUE has particular resonance for me. Juliette Binoche's attempt to cut all ties to humanity following the death of her husband and child is one of cinema's most powerful explorations of the terrible weight of our connections to other people. It is a film that means more to me the older I get.

The Colors Trilogy would be enough to lift any director into the highest rank of filmmakers, but extraordinarily enough Kieslowski has another multi-part masterpiece that many people consider his greatest work.

The DEKALOG is a ten-part series that was originally shown on Polish television in 1989. Each one-hour episode explores one of the Ten Commandments, and while some (like Murder or Adultery) are fairly straight forward in their story lines, others (like the injunction to keep the Sabbath) are more opaque. What unites all the episodes is a mastery of style and storytelling. None of the films are preachy in the slightest, and if you were to see the series without knowing the Ten Commandments framing device you might not even make the connection. Instead, you would simply see a series of films that present vividly drawn characters caught up in intriguing moral quandaries.

The DEKLOG is being released in a new set by the Criterion Collection and will be shown in select theaters, two episodes at a time. I've got my weekend planned around the DEKALOG because my beloved Music Box Theater will be showing the series starting Friday, September 2nd.

Monday, August 31, 2015

Chicago: A City of Cinephiles

Chicago stopped being a center of film production almost as quickly as it began, but it was a happening place in the early days of cinema. Carl Laemmle, founder of Universal Pictures, first began building his empire on Milwaukee Avenue. Essanay Pictures--original home of Charlie Chaplin and Broncho Billy Anderson--was headquartered here. And Chicago was the home of the two most important Black-owned film companies of the early era: George Johnson's Lincoln Motion Picture Company and Oscar Micheaux's Micheaux Film and Book Company. I could go on, but the point here is that the city played a vital role in the development of the movie industry.

Alas, its days as a movie center were numbered. There were many reasons the movie industry drifted west--to escape the Edison Trust, to take advantage of a relatively undeveloped social system that allowed for the advancement of non-WASPs--but, really, the main reason is that California had nice weather. Chicago, magnificent city that it is, has never been able to make that argument. Its winters proved too long and too brutal, so the movie industry left for a warmer climate that allowed for year-round production schedules.

Of course, a lot of movies still get made in Chicago--stuff like THE DARK KNIGHT and TRANSFORMERS on the blockbuster side, as well as indies like Joe Swanberg's HAPPY CHRISTMAS--so its appeal as a movie location clearly remains evergreen. Yet, neither Chicago's history nor its current status as a film location really explains its place in film culture.

Its vital position in world film culture is derived from its obsession with the movies themselves. It's no accident that Chicago happened to produce the most famous of all movie critics, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert. This town is movie crazy. As a place for deranged cinephiles, it can compete with any city anywhere. (I say this, of course, as a deranged cinephile.)

Here, then, are ten things this city has to offer the committed movie geek:

1. The Music Box Theater- A great old theater on Southport Avenue near Wrigley Field, the Music Box is the crown jewel of Chicago's movie world. It plays retrospectives of classic films and showcases new independents and foreign films. It has weekend midnight showings of cult classics. It hosts festivals like Noir City, The 70mm Film Festival, and The French Film Festival. It has a 24-hour horror movie marathon on Halloween. It shows silent movies the second Saturday of every month, complete with live organ music. It has big-time filmmakers come in to do events. It has a full bar. It is connected to Music Box Films which distributes foreign films in America (it brought us IDA for god's sake). It is magnificent. All on its own, the Music Box would make Chicago a damn good place to be a movie lover.

2. The Gene Siskel Film Center- Connected with the School of the Art Institute (where, full disclosure, I teach), the Siskel is the great downtown hub for movie geeks. Located on State Street, it's a truly state-of-the-art facility. It hosts festivals like the Black Harvest Film Festival, shows new independents and foreign films, and runs retrospectives year-round. All on its own, the Siskel would make Chicago a damn good place to be a movie lover.

3. Doc Films- The University of Chicago is home to the longest running student film society in the U.S. Remember how, back in the 1960s, college campuses were obsessed with movies? Well, Doc Films, which traces its roots back to the 1930s never got over its obsession. It shows everything--classics, new stuff, foreign stuff, high brow, low brow. And it's five bucks to get in. And parking is free. Sometimes filmmakers show up to present films. Back in the day, Alfred Hitchcock and John Ford showed up to present films here. This year, I saw most of Orson Welles's movies there. It's that kind of place.

4. Facets Cinematheque- An intimate theater and esoteric DVD rental shop located on Fullerton, Facets showcases small off-beat films that you can't usually find anywhere else (not even at any of the the three heavy-hitters listed above). The Cinematheque is only part of Facets Multimedia, which, among other cool things, puts on a Film Camp for kids and, for over thirty years, has hosted the Chicago International Children's Film Festival.

5. Chicago Filmmakers- Located on North Clark in the Andersonville neighborhood, Chicago Filmmakers is a not-for-profit media arts organization that "fosters the creation, appreciation, and understanding of film and video. It provides classes and workshops, sponsors screenings of avant garde or outsider films at places like Columbia College Chicago's Film Row Cinema, and puts on Reeling: The Chicago LGBTQ+ International Film Festival.

6. Northwest Chicago Film Society- I love this group, which is passionately committed to celluloid. (They bill their events, pointedly, as being "programmed and projected.") They used to show films at the beautiful old Patio Theater. Recently they've set up shop at Northeastern Illinois University. Their film series is always an electric mix of (often unsung) classics.

7. The Pickwick Theater- A gorgeous art deco theater built in 1928, the Pickwick is located in the suburb of Park Ridge. It runs new releases most of the time, but it also plays host to the Silent Summer Film Festival, powered by "our Mighty Wurlitzer Organ."

8. Century Centre Cinema- A Landmark theater specializing in independent film, the Century is spread across a couple of levels of of the Century Shopping Center on North Clark Street. It's super posh, with reclining seats and a full bar and gourmet snacks.

9. Regal City North Stadium 14 IMAX and RPX- Of course, man does not live on classics and independent films alone. Chicago has multiplexes all over the place. My favorite is the Regal on Western Ave. It's a huge place, with stadium seating, IMAX screens, and RPX (or "Regal Premium Experience") screens that have all kinds of extras and next-level sound and picture quality. They also have an amazing assortment of movie-based video games out front for the kids, including the coolest Star Wars game I've ever seen.

10. Cine-File- Check out this website devoted to providing serious criticism about whatever happens to be coming up in Chicago theaters. It's an amazing resource for local movie geeks, and it provides a nice glimpse at the depth of cinema love here.

I could really keep going. Please leave a comment if you think I've left off anything important. And I would love to be exposed to something great that I don't know about yet.

Tuesday, September 2, 2014

Noir City Chicago 6: CAGED and TENSION

Last night was another fantastic line up at Noir City Chicago 6. The Music Box Theater, in conjunction with the Film Noir Foundation, showcased two indispensable noirs: CAGED (1950) and TENSION (1949). God, what a line up. I don't know how many times I've watched these two classics, but last night was my first time to see them on the big screen and they did not disappoint. CAGED is simply a masterpiece--an all-time, top ten, noir hall of fame masterpiece. Crime films really don't get any better. And while TENSION has less unity and formal perfection (at least at the screenplay level), it is a shimmering jewel--and an enduring testament to the glorious Audrey Totter.

I've written about both movies before. Here's more on CAGED. And here's something on TENSION.

The festival is going great. It kicked off with a magnificent restoration of TOO LATE FOR TEARS (for my money, the best thing the Film Noir Foundation has done is to restore this movie), with the wonderful ROADBLOCK as a second feature. I had to miss a couple of days, unfortunately, but Sunday night I caught Jean-Pierre Melville's rarely seen 1959 TWO MEN IN MANHATTAN.

Alan Rode has been doing a crackerjack job introducing the films all week, and tonight the Czar of Noir himself, Eddie Muller, takes over. The remaining films all look terrific--including a double feature of Losey's 1951 M, followed by The BLACK VAMPIRE, an Argentinian feminist reworking of the M story. Here's the full schedule.

I've written about both movies before. Here's more on CAGED. And here's something on TENSION.

The festival is going great. It kicked off with a magnificent restoration of TOO LATE FOR TEARS (for my money, the best thing the Film Noir Foundation has done is to restore this movie), with the wonderful ROADBLOCK as a second feature. I had to miss a couple of days, unfortunately, but Sunday night I caught Jean-Pierre Melville's rarely seen 1959 TWO MEN IN MANHATTAN.

Alan Rode has been doing a crackerjack job introducing the films all week, and tonight the Czar of Noir himself, Eddie Muller, takes over. The remaining films all look terrific--including a double feature of Losey's 1951 M, followed by The BLACK VAMPIRE, an Argentinian feminist reworking of the M story. Here's the full schedule.

Wednesday, August 27, 2014

Noir City Chicago 6 and The Altars of Forgotten Women

This weekend Noir City Chicago kicks off at the Music Box Theater with two of my favorite films: TOO LATE FOR TEARS (1949) starring Lizabeth Scott and Dan Duryea, and ROADBLOCK (1950) starring Joan Dixon and Charles McGraw.

I've written about both of these films on this blog (here and here), and I'd like to reprint an essay I posted here a few years ago that celebrates Lizabeth Scott and Joan Dixon.

Here's "The Altars of Forgotten Women":

One of the ironies of

film noir is that many of its lasting icons were never stars in their lifetime.

More than any other genre, stardom in noir is retroactive. Someone like Ann

Savage had only the most fleeting taste of fame in her youth before Hollywood

showed her the door. Yet, Savage was one the lucky people who lived to see her

fame catch up to her. A cheap little sixty-five minute crime picture called

DETOUR—a picture Savage appears in for all of thirty minutes—somehow endured

and prospered over the years. Savage was in her sixties and working as a

secretary when she discovered that she was at the center of a cult.

Savage’s cult is just

a faction of something larger called film noir, which is, among other things,

largely a cult of forgotten women. Savage was not alone in finding herself as

an object of worship. Within this convocation there are many different sects,

sects with passionately devoted followers. Actors like Audrey Totter, Marie

Windsor, Evelyn Keyes, and Janis Carter all have legions of admirers. None of

them were really stars in their day, but their movies have a life all their

own. Long after their careers fizzled out, sometimes after their own deaths,

some actors finally became stars. That just about defines the word bittersweet.

Of course, major stars

like Audrey Hepburn and Judy Garland experience a similar life after death

effect, and a select few even seem to reach beyond mere stardom and become a

part of the larger shared consciousness of society. You could argue, at this

point in Western culture, that Marilyn Monroe is nearly as iconic as the Virgin

Mary.

Yet film noir is a

genre born out of B-movie obscurity. Lizabeth Scott will never be as

famous as Marilyn Monroe, but she is the ruler of her own dark little corner of

Dreamtown because is the woman who most deserves the title of Queen of Noir.

She starred in more film noirs than nearly anyone else, and she was also unique

in that her filmography consists mostly of noirs. She only made a handful of

movies that didn’t involve people betraying each other and ending up gutshot at

the end. She played the entire range of characters available to women in the

genre, from doe-eyed innocents (THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS, THE COMPANY

SHE KEEPS) to world-weary lounge singers (DARK CITY, I WALK ALONE) to

cold-blooded femme fatales (STOLEN FACE). She starred in one of the genre’s

real lowlights, the misogynistic DEAD RECKONING. She starred in what maybe the

campiest noir ever made, the hilarious DESERT FURY. Most importantly, she

starred in two of the finest noirs we have, Andre De Toth’s 1948 PITFALL and

Byron Haskin’s 1949 TOO LATE FOR TEARS.

To understand the

appeal of Liz Scott, one only need to look at those last two films. In the

first, she plays a woman named Mona Stevens who falls into an affair with a

married man played by Dick Powell. Their affair is discovered by a psychotic

private detective (played by Raymond Burr) who is obsessed with Mona and

proceeds to make life hell for everyone involved. The cast here is superb, and

at the center , in a performance of great sympathy, is Queen Liz. She makes

Mona a sexy woman (which must have been fairly easy since Scott herself was

gorgeous, blonde, and had a voice that was equal parts cigarettes and silk),

but she also makes Mona a sad woman. Loneliness is the undercurrent of Scott's

voice, the thing that pulls you further down into her trap. Even when she’s

happy, you can tell that Scott is afraid of the worst. In PITFALL, she

pretty much gets the worst at the hands of thoughtless men.

In TOO LATE FOR

TEARS, she gets her revenge. As housewife turned criminal Jane Palmer, Scott

creates a portrait of coolheaded evil. Jane and her husband Alan (Arthur

Kennedy) are driving home one night when someone tosses a briefcase full of

money into their car. Is the money a payment for a ransom? Perhaps a blackmail

payoff? Alan doesn’t care, he just wants to turn the money over to the cops.

His wife, ah, disagrees. She’s willing to do anything to keep the cash, even

after slimy crook Dan Duryea shows up looking for it and slaps her around.

Neither the crook nor the husband have any idea who they’re dealing with in

Jane Palmer. These guys are toast. With her performance, Scott makes a pretty

good grab for the most evil femme fatale on record, yet she also makes Jane

Palmer curiously relatable. Again, there’s that sadness, that aching,

unfulfilled need at the center of Lizabeth Scott that comes through in her

performance. Jane Palmer is evil, yes, but she’s also smart, dogged, and

utterly human.

It is, after all,

humanity that is the great appeal of the forgotten women of film noir, our

sense that we’re seeing a human being alive onscreen. Movies of the forties and

fifties were made to be dreamlike, and all these years later they still seem

like dreams. The dreams hook us; the humanity makes us obsessives, worshipers

at the altar. “Who was this woman?” we ask. Not just Queen Liz (who, happily,

is still alive as I write this), but so many others. We watch them laugh and

cry and scheme and die and then we watch them do it all over again. It doesn’t

take much to hook us.

Take Joan Dixon. In

1951 she starred in a vastly underrated film noir called ROADBLOCK alongside

Charles McGraw. She plays Diane, a sexy conwoman who marries a straight-laced

insurance investigator name Joe Peters, a marriage that will have disastrous

results. Joan Dixon strolls through this movie as if she’s one of the great

femme fatales. It’s not just that she’s beautiful, it’s that she projects that

essential combination of intoxicating sexual allure and an untouchable, unknowable

center. Is Diane bad? It’s tough to say. Dixon might be criticized for giving a

performance that's too laid back, but I would argue that very ambiguity is her

greatest attribute. She doesn’t set out to ruin Joe Peters, but once she meets

him, he’s a goner. It’s an interesting take on the femme fatale. Many femmes

are man-eating monsters. Diane is different. She’s a catalyst who opens up all

the insecurity and greed buried beneath honest Joe Peters’ upright façade. It

takes quite a gal to destroy Charles McGraw. Joan Dixon does it without really

trying.

One thing’s for sure:

she never had much of a career in Hollywood. She started out at RKO under

contract to Howard Hughes (which was not somewhere a fresh-faced twenty-year

old from Norfolk, Virginia wanted to find herself). Hughes promised to build

her career, but he was too busy running RKO into the ground. Dixon spent most

of her time in low budget westerns and ended her acting career in the late

fifties doing bit parts on television. By then, she’d become a lounge singer

and was mostly notable in the newspapers for a string of quick marriages

and messy divorces. She died in Los Angles in 1992.

She was no one’s idea

of the queen of anything, yet she lives on in this little-seen masterpiece. Her

fame hasn’t happened yet, unlike Ann Savage or Lizabeth Scott. Even in the

insular world of film noir, Joan Dixon isn’t an icon—yet. I have faith,

however, that her cult is coming. If there’s one thing that you can learn from

the history of noir, it’s that there’s always time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)