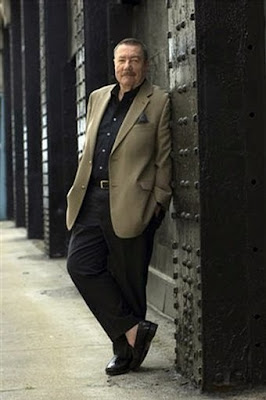

Robert B. Parker, author of the Spenser novels, died unexpectedly Monday morning. He was 77 years old. I first discovered Parker in high school when the natural process of Hammett to Chandler to MacDonald finally led me to Parker. For many people, his detective series focusing on a smart-ass private eye named for the English poet was the natural heir to the great tradition of crime-fighting American heroes.

Parker was his own man, though, and Spenser stood apart from his forefathers Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and Lew Archer. When Spenser arrived in The Godwulf Manuscript in the seventies he still smacked a bit of Marlowe and Archer, but as the years went on he began to resemble more and more the man who created him. Parker had a happy--if complicated--marriage to a woman with whom he was almost obsessively in love, so Spenser didn't stay the rugged loner very long. He met Susan Silverman, a romanticized version of Joan Parker just as Spenser was a romanticized version of her husband. Their relationship is the center of the series, a forty year examination of the challenges and glories of monogamy. As Parker had children--two sons, both gay men who work in the arts--Spenser became something of a father figure to two gay men--one a dancer, the other a cop.

Parker had a charmed creative life in which he was able to spin out exciting versions of himself and those he loved and place them within a fictional framework where things like honor and understanding were possible. This is not to say that his novels couldn't be sad--among his best books are a trilogy of novels about Spenser's failed attempts to help a prostitute named April Kyle--but they are redemptive in a way that Chandler would have found unimaginable. Parker's worldview could be warm and optimistic but it was haunted with a realization of the limitations of empathy. No man as good as Spenser ever existed, but Parker created him not as an expression of realism but as an aspiration. That's what a hero is, a secular saint, an unachievable ideal that somehow makes you feel as if such integrity were possible. Being inspirational while being funny and delivering tightly constructed fight scenes is more than most writers achieve.

I will miss Robert B Parker more than I can say. One of the consistent joys of my life was the annual fall release of the new Spenser book. It's tragic to contemplate an end to Spenser, but Parker leaves us 38 Spenser novels. They range from half-dashed entertainments to pop culture gems. He also wrote nine Jesse Stone novels, six Sunny Randall books, two Philip Marlowe books, four Westerns, and seven freestanding novels. That's a hell of a lot of writing. It's also a hell of a gift to his readers. His death is sad for those of us who have found years of comfort in his witty and wise crime novels, but one can only smile when learning that he died at his writing desk. He went out in a blaze of glory. I wrote an extended appreciation of Parker last year. You can read Notes on a Tough Guy's Legacy here.

2 comments:

I only discovered Parker upon reading of his death. In the eighteen months since then I've read over thirty of his books. I've enjoyed them all - some more than others. The only thing that bothers me about his books is his characterization of women. Except for Sunny Randall and Dr. Silverman, you can count on any woman he writes about being a slut. Why does he have such a low opinion of women?

Thanks so much for your comment! It's an interesting take, and it certainly got me thinking. I'm not sure I completely agree with your characterization of Parker's female characters as "slut(s)", though. Rachel Wallace is a strong female character. And someone like April Kyle is a lost soul whose story becomes progressively sadder as the books go forward. I don't think of her as being a one-dimensional character based around sex.

Having said that, I think Parker does return to certain character types. (This is true of both men and women.) He's fascinated with the deeply needy flawed mother-figure, for instance. Or the frigid academic. And, yes, the sex-hungry woman (often married) who throws herself at Spenser.

I'm torn two ways about Parker's tendency to recycle character types. On one hand it seems like he's doing what every author does by returning again and again to ideas and characters that clearly fascinate him.

On the other hand, Parker could be lazy. Pure and simple. He cranked out so much prose, he sometimes cut corners and got sloppy. His worst books are undercooked and slapdash affairs.

At his best, though, he could write interesting characters of both sexes. I personally don't think he has any lower opinion of most women than he does of most men (most of his supporting characters of both sexes are weak, self-deluded fools who often use sex as an escape). His true vision of perfection is, of course, Spenser and Susan. He places them as heroic ideals in a world of flawed men and women. At least that's my reading.

Post a Comment