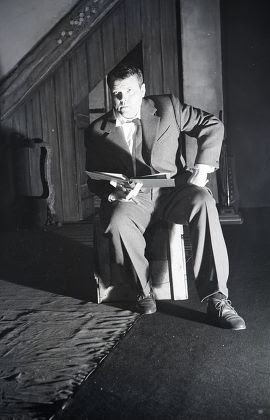

above: Welles directing MOBY DICK - REHEARSED in 1955.

If you divide the career of Orson Welles into three periods--Early, Middle, and Late--then you will find his most prolific work in theater in the Early period. That was the period of rapidly successive experiments and triumphs--the time of the Dublin Theater, the "Voodoo MACBETH," the Mercury Theater, JULUIS CESEAR, and NATIVE SON. A heady time, to be sure.

But even in his Middle period, when he'd left America and was making his way as an independent filmmaker in Europe and Africa, he did not abandon the theater. (As he would, alas, in his Late period. Although he lived until 1985, he stopped working in the theater in 1960.) In some ways, his most significant production during this time was CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT, by all accounts a failure as a play but one that functioned as a trial run for his triumphant 1965 film FALSTAFF, perhaps the single greatest work of his career.

Having said that, however, Welles' most lasting contribution to the theater during his Middle period was certainly his Melville adaptation MOBY DICK - REHEARSED. It was the highpoint of his career as a playwright and another piece of evidence that he may well have been the supreme literary 'adaptor' of the 20th century. (Other evidence would include his adaptations--on radio, stage, and screen--of HG Wells, Richard Wright, Booth Tarkington, Kafka, Isak Dinesen, and, of course, Shakespeare.) It also brings his experiments in self-conscious meta-artmaking to something of a boil, which would pay off in later works of extreme self-consciousness like his essay film F FOR FAKE and his unfinished THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND.

MOBY DICK - REHEARSED is a play in two acts. The setting is the backstage of a small theater. In Act I, we're introduced to an acting troupe getting together to rehearse a production of KING LEAR. Petty complaints and light teasing are exchanged, lines are run, a little time is killed. Then the troupe's Actor-Manager arrives and announces that they will be rehearsing a new play, an adaptation of Melville's novel MOBY DICK. The gang grumbles a little more but soon enough everyone snaps to, and the story of Ishmael, Starbuck, Captain Ahab and the great white whale begins to take shape. As it does, the story begins to take over. By Act II, we are fully in MOBY DICK, the story having subsumed the actors. Only at the very end, with Ahab and his mortal enemy confined to the watery deep, do the actors at last shrug off their roles and return to themselves. Then the curtain falls.

When Welles produced MOBY DICK - REHEARSED in June of 1955 at the Duke of York's Theater in London it garnered largely rave reviews, but it didn't draw a huge audience. (Welles, always a popular celebrity, was never a strong box office draw.) In the years since, the play has rolled on, taking on a life of its own in numerous productions (the most famous of which was the 1962 production starring Rod Steiger as the Actor-Manager/Ahab). The director of one such production in North Carolina, Robb Mann, told me that his actors played the early scenes as comedy and "then as the play progressed rolled it into drama, going from realism to hyper-realism." That strikes me as the natural progression of Welles' play, which develops from a half-hearted rehearsal to a deep immersion--with the actors playing actors who are at first playing characters until the characters finally become people who fully take over.

The adaptation itself is brilliant. With a nod to Shakespeare, Welles converts Melville's prose into blank verse. He takes the author's sprawling novel--itself a roiling compendium of styles (part philosophical meditation, part gothic comedy, part boy's adventure tale, part cetology textbook)--and pares it down to its fierce beating heart: Ahab's obsessive hunt for the whale. The crew's growing unease with their captain's obsession becomes the focal point of the play, with Starbuck's caution crashing against Ahab's mania like the waves beating the sides of the ship.

But, of course, there are no waves. There is no ship. Adapting a story like MOBY DICK to the stage is a fool's errand because you can't put the ocean or a whale inside a theater, and faking it would just look goofy. MOBY DICK works best as a novel because it works best in the theater of the mind, with Melville's incantatory prose casting its spell even when he's lecturing you about whale blubber.

Welles grasped this blunt reality and worked with it. At the start of the play, the Actor-Manager, who will transform into Ahab as the rehearsal progresses, explains to his actors that the production will involve the audience as cocreators in the evening's production. It's up to the audience to supply the ocean and the whale. This kind of stripped down theater is (to use a phrase the theater director Jerzy Grotowski would coin years later) pure "Poor Theater." It embraces economic constraints as an engine of creativity. It shows incredible faith in the audience. It also finds Welles working in direct opposition to the Brechtian notions of epic theater that characterized his Early period mega productions like FIVE KINGS (1939) and AROUND THE WORLD (1946). Both of those plays had been flops artistically and commercially, but with MOBY DICK - REHEARSED, Welles found the perfect vehicle for his particular brand of epic classical theater.

This last point is worth pondering a moment longer. As both a filmmaker and a theater producer, Orson Welles would have had a far easier time of things if he'd been interested in crafting small stories or intimate character studies. But, then again, he wouldn't have been Orson Welles, would he? He was interested in outsized personalities taking center stage on the largest possible canvas. And that never changed. FALSTAFF is as big as any movie he ever made, and he made it for a pittance.

Likewise, MOBY DICK - REHEARSED may be Poor Theater, but it's epic Poor Theater, a heedless adaptation of an unadaptable novel. It's Welles acknowledging, more than ever before, the importance of the audience as cocreators of a live performance, even for a text as iconic as Melville's book.

1 comment:

Nice article, Jake. Very interesting and informative. Too bad we couldn't see the play on Broadway with Rod Steiger. Apparently, it only ran for 13 performances. Oh, well, we still have the written play. And a better understanding now. Nice work!

Post a Comment