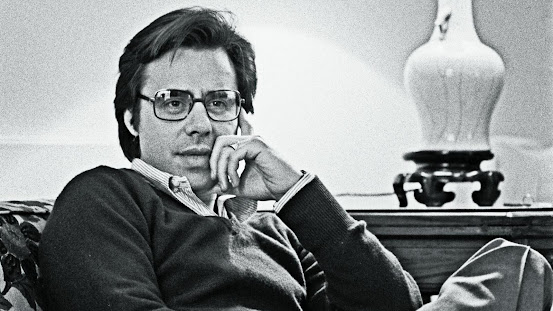

Last month, on January 6th, Peter Bogdanovich passed away. He was 82 years old, which is a nice long run, but it still seems like he was taken too soon. If you listen to almost any interview he gave over the last couple of years you'll hear him talk about the movies he still wanted to make, particularly a ghost story he wanted to film about a movie director haunted by his lost loves.

One doesn't have to dig too deeply into that plot to find the spirit of Bogdanovich himself. He was among the most personal of filmmakers, not because his life details are reflected in most of the stories he filmed (his most famous film, for example, was about growing up in Texas, an experience far removed from the life experience of a New York kid like Bogdanovich). No, his movies were personal because of his experience of making them. Like his hero and sometimes-friend Orson Welles, Bogdanovich put his passion for filmmaking onscreen. The filmmakers who most revere Bogdanovich himself--Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson, Noah Baumbach--all resemble him in this respect: the passion for the medium is the de facto subject of their work.

With Bogdanovich, of course, this stretched into his other job, that of film historian, writer, and critic. He didn't like being called a critic, and it's true that he only very occasionally functioned as one. He preferred the term "popularizer" which does seem more fitting. He rarely wrote, or even spoke on the record, about films or filmmakers he didn't like. He had a wealth of knowledge about old Hollywood, but his knowledge was idiosyncratic. He knew many of his favorite directors--Ford, Hawks, Renoir, Hitchcock, Ulmer--so he had opinions and stories about them to spare. But what about someone like Billy Wilder? Indisputably one of the great directors, Wilder and Bogdanovich had some bad blood back in the 70s, so there's barely a mention of him in any of the volumes of work Bogdanovich published on classic Hollywood. Likewise, Bogdanovich always had to be forced to say anything at all about any of his contemporaries (even ones like Francis Ford Coppola or William Friedkin with whom he had a short-lived production company). He wrote about what (and who) he liked, and pretty much ignored the rest. It was always personal with Peter Bogdanovich.

Likewise, his focus (obsession really) on directors and stars pretty much eclipsed his interest in any other area of filmmaking. Writers, cinematographers, art directors, producers (especially producers) get short shrift in his books and articles, and rarely got much mention when he was discussing his own films. The "Invisible Woman" season of the podcast YOU MUST REMEMBER THIS focusing on Bogdanovich's ex wife-and-collaborator Polly Platt is a nice corrective to the director-centric view of filmmaking that defined Bogdanovich's film histories and his interviews about his own films.

Having said all that, Bogdanovich was an auteur's auteur. The interviews he did with Welles in the book THIS IS ORSON WELLES is a primary text for any appreciation for Welles, and his interviews with classic directors in his book WHO THE HELL MADE IT? is invaluable. (One example, he conducted what might very well be the only surviving interview with DETOUR director Edgar G. Ulmer.) As a filmmaker, he was frequently brilliant, and always himself. His movies are stamped with his wit, his humanity, his passion for film, and his sensitivity to both love and the loss of love.

I hope the next year or so will bring retrospectives of his work. We need PAPER MOON, WHAT'S UP DOC?, SAINT JACK, THE LAST PICTURE SHOW, and THEY ALL LAUGHED back in theaters. I'd love the chance to see something like AT LONG LAST LOVE on the big screen, and I've always had a warm place for his expertly wrought version of NOISES OFF. Bring it all back, you art house cinemas, and let us sit in the dark and enjoy the work of one of the greats.