Frank Lovejoy was so underrated in the fifties. He was just another character actor with a pleasant face and an authoritarian voice. Today he’s probably best known to noir fans as Humphrey Bogart’s long suffering cop buddy in Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place and as one of the unsuspecting motorists taken hostage in Ida Lupino’s The Hitch-Hiker. His best role, however, was as Howard Tyler, the doomed getaway driver in Cy Endfield’s still largely unknown The Sound of Fury.

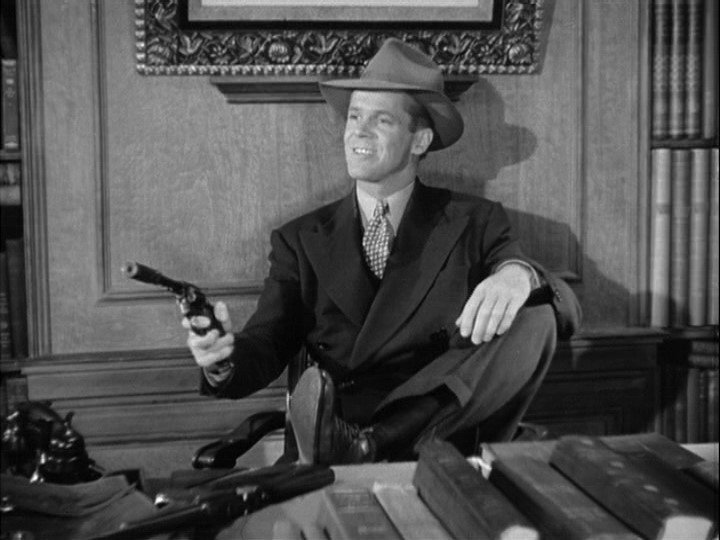

Tyler is an ex-serviceman who has recently relocated his wife and young son to California following the war. Things are supposed to be good in the sun-kissed promised land, but they aren’t. Tyler can’t get a job, and his wife’s getting fed up. He takes off one afternoon, stops by a bowling alley for a beer, and meets a guy named Jerry Slocum (Lloyd Bridges). Slocum’s a slick, fast-talking hoodlum with a business proposition for a man who’s steady behind the steering wheel. At first, Tyler has some reservations about being a getaway driver, but Jerry spells it out: take your dignity and go home broke, or stop being a sucker and go home with some cash in your wallet. Tyler thinks about it and calls his wife to tell her he’s going to be late. By midnight, he’s waiting outside a gas station while Jerry’s inside pistol-whipping the attendant.

The money flows. Tyler buys groceries. His wife is happy, and his kid wants a television set so they can watch westerns. All Tyler has to do is keep working the night shift with Jerry, but before long Jerry decides they need to upgrade from armed robbery to kidnapping. He picks the scion of a well-to-do family, and one night they nab the guy as he leaves his house.

I won’t say more about the plot except to note that in film noir there are a million guys like Jerry Slocum. He’s got meanness and a lot of ideas for getting rich. Surveying the world around him, he just sees a bunch of suckers, so he spends his days drinking beer and bowling, and spends his nights drinking whiskey and chasing dames. He thinks he’s smart, but he’s not. In noir, when you climb into a car with a Jerry Slocum you are hitching a ride to nowhere.

As Slocum, Lloyd Bridges is all vanity and violence. His preening is the perfect counterpoint to Frank Lovejoy’s sympathetic, believable portrayal as Tyler. Lovejoy has the ease of a natural onscreen everyman, but the last third of the film takes him places that are dark, frantic and surprising. It is a wonderful performance but a bittersweet reminder of how seldom Lovejoy was given challenging roles. (He seemed to have settled into television—with shows like his private eye series “Meet McGraw”—when he died suddenly of a heart attack in 1962.) Here, forming a duet with Bridges, he does the best work of his career.

The rest of the cast is hit or miss. The acclaimed Broadway actress Katherine Locke plays a disturbed spinster named Hazel, and she and Lovejoy share some nice scenes together near the end of the film. But Kathleen Ryan is shrill and whiney as Tyler’s put-upon wife. She has one good scene late in the film reading a letter from her husband, but a stronger actress in this role could have given us more insight into the nature of Tyler’s tortured decision to be a criminal. Likewise, every time little Donald Smelick opens his mouth as Tyler’s cowboy-obsessed son, I wanted him to shut up—though, in his defense, with a few exceptions most kids in noirs are generally insufferable.

The film was directed by Cy Endfield, a director who got his start as an apprentice in Orson Welles’ Mercury Productions at RKO. After Welles was driven out of RKO, Endfield wound up directing shorts for MGM, and finally got his shot at directing features at the Z-list studio Monogram. Heads started to turn for Endfield in 1950 when he made the independently produced The Underworld Story and The Sound of Fury —back to back films that were intelligent, uncompromising, and dealt with the themes of the press, mob violence, and human weakness. Unfortunately, soon after the release of The Sound of Fury, Endfield was named as a Communist sympathizer in the House on Un-American Activities Committee’s hearings on Communist subversives in Hollywood. He fled to England (where he eventually worked with fellow blacklistee Bridges), and he never retuned to work in Hollywood.

It’s damn disgrace that someone of Endfield’s talent was driven out of his profession, of course, but he left behind two impressive American films. His work in The Underworld Story is strong, but his work in The Sound of Fury is superlative. It helps that he’s working from an intelligent script by novelist Jo Pagano, whose source novel The Condemned is a sharp and underrated piece of work in its own right. Pagano intended his book, and the film that followed it, as an indictment of lynch mobs and journalistic cravenness. In both the book and the film he reaches too far in this respect (in fact he and Endfield butted heads over sections of the script Endfield felt were too didactic), but the power of its narrative comes from the way it weaves these themes in with Howard’s choice and its terrible consequences. Together, Endfield and Pagano crafted a quintessential film noir.