Saturday, December 31, 2016

My Year at the Movies: 2016

I go to the movies a lot. I started this blog about eight years ago because I wanted to have a place to think out loud about the movies I was seeing--to reflect on the old and the new, on the good and the bad. I called it the Night Editor because I tend to write late and because I like the 1946 noir NIGHT EDITOR directed by Henry Levin and starring Janis Carter (an overlooked minor gem, btw). A lot has happened for me in years since I started the blog. I've published several books, been to France twice on book tours, participated in several readings at Noir At The Bar functions, and relocated to Chicago.

But I've also seen a lot of movies. On the side of this blog I keep a running tally of how many movies I've seen at the theater. I don't know why I do this, except that going to the movies is the closest thing I have to a hobby.

This year I saw 85 movies at the theater. That's a lot, I know, (a movie about every four days), but the true measure of my cinephilic tendencies is that I don't feel like I saw enough. I still managed to miss so many interesting-looking new films and great old classics in rerelease.

I'm not someone who generally laments the state of film. Yes, schlock too often rules the box office. Yes, I worry about the reheated nature of our choices, where it seems that almost everything at the box office is a do-over of some pre-existing property. Yes, the culture is ever more infantilized. Yes, it is harder and harder to get movies made for adults.

And yet...

In some ways, things are better than we give them credit for being (and things in previous days were often worse than we give them credit for being). Here's a list of some good things about the current state of movies.

1. Hollywood has perfected the comic book movie and the sci-fi popcorn movie. A case in point: this year I saw DOCTOR STRANGE. Here's a movie that could only exist at this particular moment, the result of Marvel's mastery of the comic book movie. It has a great cast of capable actors slumming it in a labyrinth of good special effects and efficient storytelling, and the result was an entertaining afternoon at the movies. When they make the inevitable sequel, I'll check it out. Of course, I'm not saying that the Hollywood machine always gets it right. CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR was fun but overstuffed while BATMAN V SUPERMAN: DAWN OF JUSTICE was stupid and sluggish, just to take two high profile examples. But overall I think Hollywood is doing this stuff as well as it can be done. The comic book movie is the modern equivalent of the old time spectacular. Will we look back and call DOCTOR STRANGE a masterpiece? Probably not, but I really do think it will hold up better than AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS (1956) and that piece of shit won Best Picture...

2. Great stuff still gets made. This year I saw films as different as MOONLIGHT, MANCHESTER BY THE SEA, HAIL CAESAR!, ARRIVAL, CERTAIN WOMEN, and FENCES. If I'd only seen these movies, I still would have been pretty happy at the breadth and accomplishment of the year. Different movies with different tones and intentions, but so much skill and heart.

3. The revival business is going strong. I have to start here by saying that "strong" is a relative term. I'm not trying to suggest that it's 1960s-film-society strong out there, but, when it comes to classic film, I had an incredible year at the movies. Just to name a few: I saw the triumphant restoration of Welles's masterpiece CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (twice), as well as Bergman's THE SEVENTH SEAL, the Coens' BLOOD SIMPLE and BARTON FINK, Ozu's LATE AUTUMN, Kurosawa's YOJIMBO, von Stroheim's GREED, and Hitchcock's VERTIGO. The movie event of the year for me was the release of Kieslowski's DEKALOG, the ten hours of which comprised my most exciting cinematic experience this year.

I should say a few words about disappointments. In the realm of blockbusters, I think the Star Trek and Bourne franchises are in trouble. STAR TREK BEYOND was more entertaining than its horrible trailer, but the series itself is adrift. And JASON BOURNE feels every bit like a movie that knows it has no reason to exist. On the art side, Terrence Malick was back with KNIGHT OF CUPS, the kind of meandering pose-striking mess someone might make to parody Terrence Malick.

Here's my top ten new releases of the year, in no particular order:

1. MOONLIGHT-A triumph from director/screenwriter Barry Jenkins, this coming of age tale might be the most perfectly achieved new film I saw this year, with vivid camerawork and brilliant acting. Unfolding in three chapters over several years, it creates and maintains an atmosphere of emotional intensity without ever seeming to reach too hard for effect. Devastating and beautiful.

2. MANCHESTER BY THE SEA-No film I saw this year haunted me as much as this one. Director/screenwriter Kenneth Longeran tells a quietly funny and finely observed story about the ways we live with grief. Casey Affleck is a slow burning flame in the lead role as an emotionally isolated janitor dealing with the death of his older brother, and as his ex-wife Michelle Williams proves once again that she's one of the best actors working.

3. HAIL, CAESAR!-This movie divided a lot of people, even admirers of the Coen Brothers. All I can say is that it feels like a movie they made just for me, a whacked out comedy about the Hollywood studio system, with singing cowboys, dancing Communists, Jesus-obsessed studio fixers, and a goofball star of biblical epics played by George Clooney in his best comic turn in years.

4. FENCES-A world where Denzel Washington makes adaptations of August Wilson plays is a fine world, indeed. He and Viola Davis do a powerful duet here as a married couple confronting themselves, and each other, for the first time. With exceptional supporting work from Stephen Henderson and Jovan Adepo. There's talk of Washington producing more plays from Wilson's Century Cycle, which goes on the short list of things to be excited about.

5. CERTAIN WOMEN-An anthology film from director/screenwriter Kelly Reichardt based on the stories of Maile Meloy tells three different tales set in Montana. The first two stories are interesting, but the third story, about the would-be romance between a shy ranch hand (Lily Gladstone) and a young lawyer (Kristen Stewart), is a delicate heartbreaker, among the finest things that Reichardt has done.

6. ARRIVAL-This was the best sci-fi movie of the year. Sure ROGUE ONE was okay, but in a better world this deeply involving and strikingly achieved film from director Denis Villeneuve would be the one breaking records at the box office.

7. MIDNIGHT SPECIAL-Director/screenwriter Jeff Nichols makes such wonderfully quirky and specific films. This is his most daring to date, a religiously infused bit of sci-fi realism with yet another powerhouse performance from Michael Shannon.

8. WIENER-DOG-Director/screenwriter Todd Solondz is not usually my cup of cinematic tea, but this brutally funny pitch-black comedy hit me where I live. It's grim, unflinching, and hilarious.

9. LA LA LAND-From director/screenwriter Damien Chazelle and composer Justin Hurwitz, this musical comedy is a hell of a lot of fun. Some unfocused storytelling in the middle sections and some vocals-too-low-in-the-mix keep it from being completely successful, but it's carried along by good music and a stellar performance by Emma Stone.

10. NOCTURNAL ANIMALS-The final third of this twisty drama from director/screenwriter Tom Ford (adapting the novel TONY AND SUSAN by Austin Wright) has elements of a conventional (and lesser) thriller, but such is the power of this piece that I don't know what to make of them. I need to see this movie again to unravel the threads of reality and unreality that tie together its main storyline (an art dealer played by Amy Adams is shown a new novel written by her ex-husband) and the story of the novel in which a family man played by Jake Gyllenhaal (who also plays the author of the novel) seeks to avenge the murder of his wife and daughter with the help of a dying detective played by Michael Shannon (in his other great performance of the year).

Other good films I saw this year included the riveting documentary WEINER, the coolly unsettling THE LOBSTER, the effective Blake Lively-versus-Jaws thriller THE SHALLOWS, the fun GHOSTBUSTERS reboot, the happily trashy THE NICE GUYS, the well-acted rural noir HELL OR HIGH WATER and the quirky western IN A VALLEY OF VIOLENCE featuring a wonderful scene-stealing performance from John Travolta as the morally conflicted, and often laugh out loud funny, bad guy.

In addition to those already mentioned, some of the best revival movie experiences I had this year included seeing my beloved PAPER MOON (1973) on the big screen for the first time; discovering Stephanie Rothman's deeply subversive THE STUDENT NURSES (1970) and Peter Fonda's trippy THE HIRED HAND (1971); and revisiting Billy Wilder's hilarious ONE, TWO, THREE (1961), Bogart's final film THE HARDER THEY FALL (1957) and Scorsese's masterpiece TAXI DRIVER (1976). My best discovery at the revival movies was the Nicholas Ray rodeo drama THE LUSTY MEN (1952) which features the best Robert Mitchum performance that most people haven't seen.

All in all, it was a damn good year at the movies. The year ahead looks foreboding in many ways for our politics and our society. We need the movies more than ever, and here's hoping 2017 will find me (and you) in the dark, staring up at the big screen.

Thursday, December 8, 2016

Merry Christmas from the McClanes: DIE HARD 2: DIE HARDER (1990)

When it was released in 1990, DIE HARD 2 was greeted as a rehash of the original 1988 film. Fair enough. The story finds John McClane (Bruce Willis) stuck at Dulles International Airport at Christmas, once again bringing in the Yuletide by saving his wife Holly (Bonnie Bedila) from terrorists. In retrospect, though, DIE HARD 2 is clearly the best of the DIE HARD sequels, the only film in the series to really extend the charm and excitement of the first film.

Before I explain what makes it the only worthy successor to the original, I suppose we should dispense with the rest of the sequels:

DIE HARD WITH A VENGEANCE (1995) was seen by many as a return to form for the series, with DIE HARD's director John McTiernan taking back the helm from DIE HARD 2's Renny Harlin. But seen today, VENGEANCE is more dated, a relic of the 90s. It has a gimmicky plot (McClane and a post-PULP FICTION Samuel L. Jackson are forced to solve puzzles by a criminal mastermind like they're facing off against the Riddler), a dull villain (making Jeremy Irons the brother of Alan Rickman's Hans Gruber just draws attention to how much better Rickman was in the first film), some clumsy racial politics (McClane, a NYC cop, teaches Jackson, a middle-aged black man, how not to be such a racist), and a sloppy third act (reshot almost entirely, it feels rushed and lifeless at the same time). There are some good scenes here and there (the shoot out in the elevator, chief among them), but the film is overlong, tired, and talky. Worse still, it marks the turning point in the series when McClane goes from being a likable everyman to being a grumpy lunkhead.

Things just get worse in LIVE FREE OR DIE HARD (2007), a sequel caked with 12 years of dust. This time McClane teams up with a hacker played by Justin Long to rescue McClane's daughter (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) from bad guy Timothy Olyphant. In some ways, LIVE FREE is the worst of the series. For one thing, McClane's not really the main character. He's just here to be the grumpy old sage to Long's morally conflicted hacker, the only character in the movie with an actual story arc. For another thing, this is the point in the series where McClane stops being a recognizable human with the capacity to be hurt. He stands on a spinning jet plane, jumps out of a speeding car onto pavement at 80 miles an hour, shoots himself in the chest at point blank range, ect, all without doing more than grimacing. Add in Olyphant's bland villain and a PG-13 rating, and you get a series in freefall.

Last and least is 2013's A GOOD DAY TO DIE HARD, which finds McClane traveling to Russia to help his son (Jai Courtney) fight some terrorists. Wheezing and out of ideas, the film dusts off the McClane-reunites-with-his-estranged-family plot for the fourth time to zero emotional effect. We've seen this blood-soaked McClane family reunion before, but the father-son dynamic only encourages the filmmakers to up the macho bullshit, and so we have John and John Jr. dropping off buildings through fifty layers of glass and fire, only to emerge strutting and laughing at the end. A cold and stupid movie, GOOD DAY is a long, long, long way from the first film, the most riveting scene of which involved McClane pulling a single shard of glass from his foot and tearfully confessing his love for his wife. The 2013 McClane, by contrast, is a video game character, endlessly rebooting to the same level of physical invulnerability and emotional obstinacy.

Which brings us back to DIE HARD 2. It's the only sequel that doesn't rehash the family dysfunction plot. Instead, it accepts the happy ending of DIE HARD and builds on it. John and Holly, despite only sharing a single scene at the end, are a likable couple, flirting on the phone at the start, and rising to the challenge in parallel storylines when everything goes wrong.

Speaking of the "going wrong" part: while William Sadler is no Hans Gruber (hey, nobody is), his cold right-wing terrorist Col. Stuart is the only post-Hans villain who seems to pose an actual threat to McClane. The scene where he downs a commercial jetliner, killing hundreds of people on board, is one of the most effecting scenes of villainy in the series.

Renny Harlin directs the action scenes here with speed and precision, while keeping McClane within the general vicinity of recognizable humanity. Where the first film found him shoeless and shirtless (which rendered him more exposed than the typical action hero), this one finds him gasping for breath and shouldering against the cold as he runs all over the snowbound airport fighting bad guys. The shootout on the conveyor belt is particularly effective because Willis plays it scared. Pinned down under some collapsed scaffolding, he desperately crawls for a gun as a goon charges at him. That moment of fear -- the "if I don't get this gun that guy is going to kick my ass and kill me" -- doesn't really have an analog in the later films in the series. The McClane of DIE HARD 3, 4, and 5 can be wounded, but he can't be scared because he's lost the ability to die.

DIE HARDER features Willis's lightest turn as McClane. He's flirtatious (with both his wife and a pretty girl at the airport), he's still funny (muttering to himself, "Oh, we are just up to our ass in terrorists again, aren't we, John?"), and he's resilient in the action scenes without being superhuman (I've always loved that in the final fight on the wing of the plane with Sadler, he more or less gets his ass kicked). He's still, well, John McClane, a character you enjoy spending time with, a guy you can root for because you like him.

The original DIE HARD is a masterpiece of its kind, one of the best action movies ever made, going on a shortlist with films like RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, THE BOURNE ULTIMATUM, and, more recently, MAD MAX: FURY ROAD. IF DIE HARDER doesn't quite belong in that elevated company, it still deserves to be seen as a worthy successor to the original. It's a movie that doesn't take itself too seriously, a holiday action blockbuster sequel that understands what it is trying to do (i.e. rip off the original) and manages to do so without turning dour or cynical in the process.

Friday, November 11, 2016

The Death of a Moderate: My Radicalization

I was not born to be a radical. I hate confrontation in all its forms, and I am by nature and inclination a peacemaker. Temperamentally, I'm a mild mannered man who descends from a line of mild mannered men. I like quiet, even solitary, pursuits: writing and reading books, watching movies, listening to music, looking at and thinking about art. I am not a religious man, except in the sense that I think that faith, hope, and charity are the greatest of all virtues, and that how you treat the poor, imprisoned, hungry and sick is a pretty good indication of how close you are to the kingdom of heaven. I tend toward moderation, and I don't like to see people get upset. So, no, I am not a natural born radical.

But we find ourselves in radical times. The election of 2016 isn't just another election. I take the President-elect at his word. I think he means to do the things he has said he will do. Will he succeed at shattering families by building a wall, or deporting millions of people, or instituting a religious test? Will he further normalize torture and surveillance, atrocities for which he's stated admiration? Will his administration pursue the anti-LGBT policies outlined in the new Republican platform? With his picks for the Supreme Court and the Cabinet, will he strengthen the police state and the prison/industrial complex while weakening our civil liberties and environmental protections? I don't know. He's a man who has bankrupted several businesses, including a casino, so his management abilities are suspect. But I take him at his word that he will attempt to do these things, and I believe that his team of political castoffs and alt-right xenophobes, as well as his most fervent supporters in the swamp of white nationalism, all mean business. I take them at their word.

So I am being radicalized. I've been a vaguely left-of-center guy for about half my life now, after having been a vaguely right-of-center guy for the first half. Now, at last, I am a leftist. I have to be. I have no choice. Implicitly or explicitly, the Trump campaign has trafficked in various bigotries since it kicked off last year: race-baiting, immigrant bashing, misogyny. Now this grotesque parade has marched into Washington and will soon take the reigns of power. There can be no moderation in the face of this kind of evil. There is only acquiescence or resistance. I choose resistance.

Ironically, I've also been radicalized because in one profound way the President-elect's supporters are actually correct, whether they realize it or not, and this has clarified for me what is wrong with the American Left. The election of Donald Trump proves once and for all, if we're smart enough to see it, that neoliberalism is a failure. The slide from New Deal liberalism (which, we should never forget, sprang up as a corrective to the hyper-capitalism of the 1920s) to our current state of privatized cronyism has been long and ugly, but the worst of it has transpired in my lifetime.

From Bill Clinton to George W. Bush to Barack Obama, the government has propped up Wall Street's financial services industry, fueling reckless casino capitalism. This system very nearly imploded in 2008, the natural collapse of greed and stupidity, but it was saved at the last minute by Bush and Obama. This age of rewarded incompetence will not come to an end under Trump, a man whose entire life is a testament to rewarded incompetence. Likely it will get worse, as will, I suspect, most things. Neofascism is the worst possible antidote to neolibralism, yet it is rushing to fill the void that decades of failed economic and social policy--not to mention a now permanent state of war--has blown open in our national culture. It makes perfect sense that a carnival barker con-man like Donald Trump would be the one to step in to take charge of this pyramid scheme.

Earlier this year, I read William Shirer's THE RISE AND FALL OF THE THIRD REICH, long before it occurred to me that Trumpism was any kind of real threat. (I don't think Trump's another Hitler, by the way, despite his Nazi admirers. Hitler was a fanatic, and Trump is too venal to ever be a fanatic. A lazy bigot and a desperate narcissist, he is more Mussolini than Hitler.) One of the things that Shirer's book makes clear, however, is that the path to fascism is paved by the weakness and corruption of the preceding governmental system.

We can see how this weakness played out in America. As conservatives drifted further and further to the right over the last twenty years they pulled the center with them, and neoliberalism (the dominate political force on the left since the 1990s) helped to create the very economic and social problems that Trump's racist xenophobia promised to fix. Trump's immigrant-blaming and wall-building are shell games, dumbed down answers to legitimate fears about our increasingly complicated world. But Neoliberalism didn't offer answers at all. It only offered to stay the course, a steady hand on the tiller of a sinking ship.

So I am radicalized, against the neofascists moving to Washington, but also against the neoliberals who will either be powerless to stop the tide of shit coming our way or who will, in all likelihood, cravenly attempt to ride it.

Where will my radicalization lead me? I don't know yet. I've been a radical for about a day and a half. Give me a minute. I'm just now starting on this journey. Hell, I'm still packing my bags. The one thing I know is that I can't stay where I am. That's not an option anymore. I must move.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Sunday, October 16, 2016

RIP Ed Gorman

Sad to hear that Ed Gorman has passed away. I was lucky to get to know him a few years ago. No one knew more about crime writing, and crime writers, than Ed. The last time we talked he told me a funny story about interviewing Margaret Millar, and then he trashed Donald Trump for a while, calling him a cut rate con man. Classic Gorman. Ed was a legend in his own right, as both an author and an editor, but the thing I'll remember most about him was how incredibly generous he was. You'll hear this, I am sure, in the tributes that will come out of the next few days. Ed was so supportive to up and coming writers, and he was living proof that talent and kindness can go hand in hand. He will be missed.

Friday, October 7, 2016

HELL ON CHURCH STREET

Go tell it on the mountain, HELL ON CHURCH STREET is back!

After switching publishers in the spring, the book will make its debut over at its new home of 280 Steps, on October 18th. In the years since this book was first released, I've been on one long wild ride, and I'm absolutely thrilled about this new phase in the criminal career of Geoffrey Webb.

Thursday, September 29, 2016

Back In The USA

I should thank everyone involved--all the booksellers, readers, and organizers. You all have my sincerest gratitude.

Thursday, September 1, 2016

Book Tour In France!

France, I am coming for you.

Jake Hinkson est l'invité de la Médiathèque départementale des Landes et participera à une série de rencontres en France. Vous pourrez le rencontrer :

- le 15 septembre à la librairie Les Mots et les choses de Boulogne-Billancourt

- le 16 septembre à la Librairie du Tramway à Lyon

- les 17 et 18 septembre au Festival Le Polar se met au vert organisé par la Médiathèque départementale des Landes

- le 20 septembre à la librairie Hirigoyen de Bayonne

- le 21 septembre à la librairie Tonnet de Pau

- le 22 septembre à la librairie Campus de Dax

- le 23 septembre à la librairie Caractères de Mont-de-Marsan

- les 24 et 25 septembre au Festival Polar en cabanes à Bordeaux

- le 15 septembre à la librairie Les Mots et les choses de Boulogne-Billancourt

- le 16 septembre à la Librairie du Tramway à Lyon

- les 17 et 18 septembre au Festival Le Polar se met au vert organisé par la Médiathèque départementale des Landes

- le 20 septembre à la librairie Hirigoyen de Bayonne

- le 21 septembre à la librairie Tonnet de Pau

- le 22 septembre à la librairie Campus de Dax

- le 23 septembre à la librairie Caractères de Mont-de-Marsan

- les 24 et 25 septembre au Festival Polar en cabanes à Bordeaux

For more information, check out my author page at the Gallmeister website.

Sunday, August 28, 2016

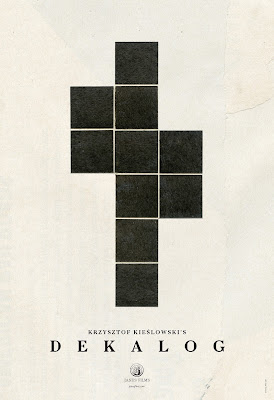

DEKALOG (1989)

Deep down, in my heart of hearts, Krzysztof Kieslowski might well be my favorite filmmaker. I can't think of a director whose work I find more beguiling, more entrancing, and, ultimately, more human.

I think his greatest accomplishment is the so-called Colors Trilogy: BLUE (1993), WHITE (1994), and RED (1994). BLUE has particular resonance for me. Juliette Binoche's attempt to cut all ties to humanity following the death of her husband and child is one of cinema's most powerful explorations of the terrible weight of our connections to other people. It is a film that means more to me the older I get.

The Colors Trilogy would be enough to lift any director into the highest rank of filmmakers, but extraordinarily enough Kieslowski has another multi-part masterpiece that many people consider his greatest work.

The DEKALOG is a ten-part series that was originally shown on Polish television in 1989. Each one-hour episode explores one of the Ten Commandments, and while some (like Murder or Adultery) are fairly straight forward in their story lines, others (like the injunction to keep the Sabbath) are more opaque. What unites all the episodes is a mastery of style and storytelling. None of the films are preachy in the slightest, and if you were to see the series without knowing the Ten Commandments framing device you might not even make the connection. Instead, you would simply see a series of films that present vividly drawn characters caught up in intriguing moral quandaries.

The DEKLOG is being released in a new set by the Criterion Collection and will be shown in select theaters, two episodes at a time. I've got my weekend planned around the DEKALOG because my beloved Music Box Theater will be showing the series starting Friday, September 2nd.

Sunday, August 14, 2016

Noir City Chicago 8

The biggest thing that happens for me moviewise every year is the annual Noir City Chicago put on by the Film Noir Foundation at the Music Box Theater. It's a can't-miss festival of classics and oddities, and this year's line up (starting this Friday) looks amazing. Stand outs include the Charles McGraw flicks ARMORED CAR ROBBERY and THE NARROW MARGIN, the Ida Lupino rarity DEEP VALLEY, the Martin Goldsmith penned SHAKEDOWN with Howard Duff, and Bogart's last film, the boxing flick THE HARDER THEY FALL.

Here's the complete schedule of movies and showtimes.

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

MISCHIEF by Charlotte Armstrong

Note: This piece originally appeared at The Life Sentence.

All literary genres tempt their

authors toward certain shortcuts — not just clichés of plot or characterization

but clichés of meaning. Whereas the western often basks in white male

triumphalism, and the romance leans on selective notions of destiny, the roman

noir slouches toward a simplistic form of pessimism. Another way of saying this

is that all genre fiction can be guilty of telling us what we want to hear, and

this is no less true of a gloomy genre like noir than it is of a sunny genre

like the romance. Pointing this out is not to indict noir, just to acknowledge

the nature of the beast. The laziest purveyors of noir truck in a kind of

reflexive cynicism that is every bit as false as a tacked-on happy ending. What

great noir writers do, in contrast, is to explore the tension between order and

chaos, revealing the danger and doom they see lurking beneath society’s

reassurances about law and order. They reveal the darkness at the edge of the

light without denying the light or turning the darkness into a gimmick.

Take Charlotte Armstrong, a

writer whose books are a mixture of light and darkness, hope and hopelessness. In

her best work, people grapple for meaning and stability in a world that seems

to be flying apart. Her books seldom end in utter despair, though. Instead, Armstrong

was the master of lingering dread. Even when her plots resolved themselves in

reassuring ways, her characters were left with a hard won knowledge of life’s

precariousness.

Armstrong’s mastery of these

different tones has its roots in her previous writing life. Although she was

eventually heralded as one of the genre’s greatest writers, she actually came

to crime fiction rather late. Before she published her first novel, she’d

written journalism, poetry, and plays. By all accounts —and this is no surprise

— she was good at every literary endeavor she put her hand to, but it was the

need to make a living that finally steered her toward the potentially lucrative

field of mysteries. She was 37 when she published her debut novel LAY ON,

MACDUFF! in 1942. In her early novels, fairly conventional whodunits featuring

an historian-turned-detective named MacDougal Duff, one can see Armstrong

getting her footing in the mystery genre. While the Duff books are

entertaining, if she had stayed with them it’s doubtful she would be remembered

as fondly as she is today. She soon abandoned the whodunit in favor of more

complex suspense stories, and once she began writing books that we now define

as noir, Armstrong hit her artistic stride.

She was an immediate hit, and Hollywood

came courting early when director Michael Curtiz adapted her novel THE

UNSUSPECTED in 1947. Although Armstrong got enough work in movies and

television that she moved to California to be closer the business (where she

wrote for Alfred Hitchcock and Ida Lupino, among others), she never stopped

writing novels. In 1963 alone she published four books. Even more striking than

her prolificacy, however, was the consistent quality of her work. In 1968, for

example, two of her books were nominated for the Edgar for Best Novel. By the

time she died of cancer in 1969 — finishing her final novel quite literally on

her deathbed — she was a legend.

It is fitting, then, that

Armstrong is among the writers being honored by the Library of America in the excellent

new collection, Women Crime Writers of the 40s and 50s. Edited by Sarah Weinman,

the boxed set includes a murderer’s row of noir greats represented by some of

their best works: Vera Caspary (LAURA), Helen Eustis (THE HORIZONTAL MAN), Patricia

Highsmith (THE BLUNDERER), Dolores Hitchens (FOOL’S GOLD), Elisabeth Sanxay

Holding (THE BLANK WALL), Dorothy B. Hughes (IN A LONELY PLACE), and Margret

Millar (BEAST IN VIEW).

Armstrong’s addition to the

collection is her slim masterpiece MISCHIEF. While she was never afraid of a

convoluted plot (her 1946 novel THE UNSUSPECTED has a plot so labyrinthine it

could have been designed by Daedalus), here she keeps things deceptively

simple.

Ruth and Peter Jones are from the

small town of Brennerton, where Peter is the editor and publisher of the local

paper. They’re visiting New York so Peter can give a speech at a convention of

newspapermen. When the babysitter for their young daughter Bunny cancels at the

last minute, the hotel’s friendly elevator operator, Eddie, offers his niece,

Nell, for the job. But Nell is not what she seems…

As Jeffrey Marks writes in his

book ATOMIC RENAISSANCE: WOMEN MYSTERY WRITERS OF THE 1940s AND 1950s, “MISCHIEF

would do for babysitters what PSYCHO did for the shower.” Nell seems to have

been born inside every parent’s worst nightmare. She starts out slow: banishing

Bunny to bed, rifling through the Jones’ things, trying on Ruth’s negligee and

perfume, prank calling random housewives by asking to speak to their husbands.

Then things escalate. When she spies a handsome stranger through the window,

she invites him in for a nightcap.

The man’s name is Jed Towers, and

he’s in for the worst night of his life. He’s just had a fight with his

girlfriend, Lyn, and he’s all too happy to be invited up to a pretty woman’s

room for a couple of drinks. As soon as he’s in the hotel room and the booze

starts flowing, however, things spiral from strange to crazy to outright

terrifying. The woman is younger than he thought, weirder than he thought. When

little Bunny wanders in on their little scene, Nell flies into a rage that

turns Jed’s odd night into an outright nightmare. Jed thinks he’s a

freewheeling man of independence until he meets someone who truly doesn’t care

about anyone but herself.

The most striking element of the

book is its expert construction. Armstrong has an unerring instinct for the

right place to break a scene, the right time to shift perspective. Either

dramatically or subtly, every scene adds to the rising tension. The book also

shows off Armstrong’s ability to perfectly capture characters in a line or two.

She writes that the would-be ladies man Jed is “one of those young men who had

come out of the late war with that drive, that cutting quality, as if they had

shucked off human uncertainties and were aimed and hurtling toward something in

the future about which they seemed very sure.” In contrast to this macho

self-assurance she describes the elevator operator Eddie as an “anxious little

man, the kind who keeps explaining himself though nobody cares.”

MISCHIEF moves with such expert

precision that it’s easy to miss how much it’s doing. The book in some ways is

a study of the way people carry themselves and the way anxiety bubbles beneath

every façade. Everyone is anxious: Peter is nervous about his speech, Ruth is

nervous about her daughter, Lyn is nervous about Jed, Eddie is nervous about

Nell. Even the smooth Jed spends the entire book thrown off his game, first by

Lyn’s insistence that he’s “cheap cynic” and then by Nell’s nihilistic

instability.

The only person who doesn’t spend

the book choking with tension is Nell. When we first meet her, she’s a strange,

quiet girl, 19 or 20, with hair “the color of a lion’s hide.” Peter is too

distracted by his upcoming speech to pay much attention to her, but Ruth is

immediately unsettled by Nell’s complete lack of affect. “Eddie’s interposing

chatter was nervous, as if it covered something lumpish and obstinate in the

girl, who was not helping.” Peter is able to convince his wife to leave, but

Armstrong tells us, “Not all of Ruth went through the door […] A part of Ruth

lay, in advance of time, in the strange dark.”

Nell isn’t simply a psychopath

who terrorizes a little girl and threatens to ruin the life of a hapless man.

She is a trigger for the fears of everyone around her; her very lack of concern

throws everyone else into chaos. The thing that makes Ruth suspicious of Nell

to begin with is her lack of underlying anxiety, a complete absence of a need

to please. This oddness might be written off as mere rudeness, or even a sign

of deep self assurance. Later when Jed is trapped inside the hotel room with

her, however, he has a subconscious realization of what exactly is missing in

her, the ability to connect her actions with their consequences:

[T]here

is something wild about total immersion in the present tense. What if the

restraint of the future didn’t exist? What if you never said to yourself, “I’d

better not. I’ll be in trouble if I do?”

Not subject to any underlying

middle-class fears, and oblivious to the possible repercussions of her actions,

Nell is pure id, a vision of teenaged recklessness raised to a nightmare

boiling point. To understand the anxiety of a decade that would produce the

juvenile delinquent movie to compliment a trend in increasingly authoritarian

crime films, look at the terror represented in this emotionally unhinged babysitter.

MISCHIEF was a hit when it was

first released in 1951, and it earned raves from the critics, including a

reviewer for the New York Times who called it “One of the finest pure

terror-suspense stories ever written.” Hollywood snapped up the book, and the

following year Marilyn Monroe had her first starring role as Nell in an adaptation

of the book called DON’T BOTHER TO KNOCK.

In the decades after her death,

Armstrong, along with writers like Elisabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret

Millar, never fully disappeared from public view, though their posthumous fame

dimmed quite a bit when compared to someone like Patricia Highsmith, whose fame

has only grown since her passing. Happily, with the release of the Library of

America’s Women Crime Writers of the 40s and 50s, Charlotte Armstrong and MISCHIEF

are poised to gain a new generation of fans.

Thursday, July 28, 2016

HUMAN DESIRE (1954)

In the forties and

fifties, Fritz Lang had a nice little sideline remaking Jean Renoir movies. In

1945, he remade Renoir’s LA CHIENNE as SCARLET STREET with Edward G. Robinson

and Joan Bennett, and the result was one of the finest films in the noir canon.

In 1954, he remade LA BETE HUMAINE as HUMAN DESIRE with Glenn Ford and Gloria

Grahame. The results, if not a masterpiece like SCARLET STREET, are still quite

impressive.

HUMAN DESIRE centers

around the marriage of Carl Buckley (Broderick Crawford)—a big lug of a guy

with a quick laugh and a hot temper—and his sexy young wife, Vicki (Grahame). Things

are okay between Carl and Vicki. He works hard and unhappily at the railroad

while she sits around the house looking sexy and waiting for him to come home.

Then one day, in a tantrum, he quits his job. By the time he gets to the house,

he’s already in a panic and desperate to get his job back. Specifically, he

wants Vicki to get it back for him.

Reluctantly, she agrees. She

goes to see Carl’s boss, sleeps with him, and gets her husband his job back. But

that, it turns out, wasn’t quite what Carl had in mind. In a cold, controlled

rage, he forces Vicki to help him murder the guy.

From there, their

marriage spirals into a nightmare. Carl drinks all day, beats Vicki at night,

and then begs her forgiveness. She only takes this so long before she sets her

sights on Jeff (Glenn Ford), one of Carl’s coworkers. Jeff’s a nice guy who’s just

back from Korea, but when he meets Vicki you can almost see the steam rise off

his face. Before long, Vicki is crying on his shoulder and pulling him toward

the bedroom. Once Jeff has seen the promised land, Vicki more or less orders

him to kill Carl.

This movie reunited Fritz

Lang with Ford and Grahame a year after the three of them had made THE BIG HEAT.

Most noir aficionados prefer THE BIG HEAT, and HUMAN DESIRE also suffers from

constant comparisons to Renoir’s original LA BETE HUMAINE. The comparisons

between the three movies is understandable, but they obscure the fact that, by

itself, HUMAN DESIRE is a brutal little triangle of lust and murder. Ford, Broderick,

and Grahame are quite good, with Gloria in particular really digging deep.

She’s a femme fatale here (a switch from the usual whore-with-the-heart-of-gold

role she was confined to for much of her career), but she makes the character a

believable combination of sexiness, cowardice and cold-blooded calculation.

Vicki’s not a bad person, not exactly. She’s just bad news. If her husband

hadn’t lost his job, they might have gone on happily for a long time, but when

things do go wrong, she goes wrong with them. In showing how a femme fatale is

born from circumstance and bad character, Grahame gives one of her great

performances.

The chief criticism to

level against the film is that it bails out at the end. Whereas in films like SCARLET

STREET and, earlier, in M, Lang was able to see his dark vision though to the

end, here he pulls back a little. The ending, though dark and gritty, still has

the tease of Hollywood uplift.

Still, there is a lot

here to appreciate. Lang could be an uneven director, but there is no doubting

his enormous gifts. From the murder in the darkened train car, to Grahame’s

post-coital seduction of Ford—turning him from an illicit lover to a would be

murderer—Lang’s management of scenes is always brutally effective. This may not

be the best film he made, but it is an underrated piece of work.

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

A Good Man In A Bad Time: THE LIVES OF ROBERT RYAN

The 1951 crime

flick THE RACKET is one of film

noir’s

great misfires. Robert Mitchum stars as an honest cop trying to bring down

vicious crime lord Robert Ryan, and with these two titans of noir squaring off

against each other, the film should be a blast. Instead, it’s a

disaster. Under the obsessive and erratic supervision of RKO studio chief

Howard Hughes, the film was shot, reshot, and reshot again. The story changed

every time Hughes changed his mind, which was almost daily. Burning through

five directors and countless yards of film, Hughes managed to squeeze all the

life out of what should have been a fun little gangster picture. The result, by

pretty much any measure, is a mess.

Today, the only

fun thing about THE RACKET is

the opportunity to observe the interaction of the two stars who, together,

define the opposite ends of film noir’s emotional scale: Robert Mitchum and Robert

Ryan. Mitchum was, of course, forever the king of cool, his breezy insouciance

acquiring a kind of romantic sheen in classics like OUT OF THE PAST (1947). While Mitchum’s

very lack of concern could occasionally curdle into a pathological absence of

empathy (in films like THE NIGHT OF THE HUNTER or CAPE FEAR), for the most part film noir positioned his

detachment as something cool. When Lee Server wrote the definitive Mitchum

biography, he snatched one of the actor’s great OUT

OF THE PAST lines for his title: BABY,

I DON’T CARE

Robert Ryan, on

the other hand, wasn’t cool. He was hot. He rarely got to play the good

guy, and he had even fewer chances to play romantic leads. He was noir’s

man on the edge. He specialized in playing desperation, bigotry, and psychosis

(on one occasion he even played a vicious version of Howard Hughes himself).

When he did get to portray the hero, in classics like THE SET-UP or ON

DANGEROUS GROUND, he brought real fire and passion to his roles. Robert

Ryan never played indifference onscreen. Detachment was never his thing. Good

or bad, Robert Ryan always cared, baby.

In his

wonderful new biography of the actor, THE

LIVES OF ROBERT RYAN, Chicago Reader critic J.R. Jones makes clear that

Ryan’s

onscreen passion was very much in keeping with his offscreen life. One of the

most politically engaged actors of his era, Ryan charted his own course through

some of Hollywood’s darkest days, and along the way made himself

into an enduring icon of film noir. With THE

LIVES OF ROBERT RYAN, we now have the kind of serious treatment which

Ryan has always deserved.

Born into a

well-to-do family in 1909, Robert Bushnell Ryan was raised on Chicago’s

north side. Jones reveals that Ryan’s father was a successful businessman who was

deeply involved in the rough-and-tumble politics of the city’s

Democratic machine. Young Bob kept his eyes open, and although he would grow

into a far more idealistic man than his father, he inherited a steel spine and

a practical streak when it came to navigating choppy political waters.

Unfortunately,

while he was still young, a series of tragedies struck his family that would

shape his inner life for years to come. When he was still a child, his younger

brother Jack died. His parents closed ranks around their surviving son, but

Jones notes that they were “Victorian people, reserved even with their own

child; and as the years passed Bob learned to keep his own company.”

Even as an adult, even with those he loved the most, Jones reports, Ryan would

remain “a

sealed envelope.”

Bob had gone

away to Dartmouth — studying English in the hopes of being a

playwright, and becoming a collegiate boxing champion in the meantime — when

tragedy struck again. First the stock market crashed, and the Ryan family

fortune was wiped out. Not long after, a fire broke out on one of his father’s

job sites, killing eleven men and delivering a blow the Ryan family business

never recovered from. After graduating from school, Bob kicked around for a few

years, scribbling away at his plays and working a variety of jobs, including a

short stint as a male model and a failed attempt at gold prospecting in

Montana. Out west he worked on a dude ranch and learned how to handle a horse (experience

that would come in handy once he started making westerns). He was working as a

sailor on the boat The City of New York, making runs between New York, and

South Africa, when he learned that his father had died after being hit by a

car. With this final family tragedy, Robert Ryan had to settle down and find a

career.

He got into

acting through the instigation of a friend. Jones quotes Ryan as saying, “I

never even thought of acting until I was twenty-eight. The first minute I got

on the stage I thought, ‘Bing! This is it.’” He quickly made his way to Hollywood

and into the tutelage of the legendary acting coach Max Reinhart. Even more

important for Ryan, at the Reinhardt School of the Theater he met an aspiring

young actor named Jessica Cadwalader, who would shortly become his wife.

One of the main

pleasures of THE LIVES OF ROBERT RYAN

is the attention Jones pays to the fascinating figure of Jessica Ryan. The

pacifist daughter of Quaker parents, Jessica was a serious and well-read woman

who spurned the Hollywood social set in favor of political and intellectual

pursuits. Soon after she married Ryan, she quit acting and devoted herself to

writing mysteries (like THE MAN WHO

ASKED WHY, 1945; and EXIT HARLEQUIN, 1947). After giving birth to two sons, she

began to turn her attention to the field of childhood education. Around the

time she gave birth to the Ryans’ third child, a daughter, she had already put

plans into motion to open a progressive grade school in North Hollywood. The

Oakwood School, as it would come to be called, became a passion for both

Jessica and her husband.

Before that

time came, however, the Ryans had to get through World War II. When the war

broke out Bob’s

movie career was just catching fire with a couple of roles that let him take off

his shirt and demonstrate his boxing skills. Jessica wasn’t

happy when he entered the Marine Corps as a drill instructor; although once the

war ended and the Red Scare overtook Hollywood, Bob’s

military service would provide him with political cover from conservatives who

didn’t

like his lefty politics.

The Red Scare,

and the blacklist period that it birthed, features prominently in THE LIVES OF ROBERT RYAN for good

reason. The book nicely situates Ryan’s film noir career in the rising turmoil of the

postwar world. Ryan didn’t make his first noir until 1947 — the

genre’s

pivotal year — when he starred in Jean Renoir’s

convoluted THE WOMAN ON THE BEACH

opposite Joan Bennett. That same year he would make CROSSFIRE for Edward Dmytryk, opposite Robert Mitchum,

and the following year he would star in the underrated Fred Zinnemann

masterpiece ACT OF VIOLENCE.

All three of these noir films cast Ryan as a violent (or potentially violent)

ex-serviceman. By 1947, he was practically the onscreen face of what we now

know as PTSD.

Of course, 1947

was also the same year the House Committee on Un-American Activities came to

town. The

Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, an

organization of Hollywood conservatives led by John Wayne, warned the committee against creeping communist

influence in the movie industry. Congressional subpoenas were issued. A group

of leftist filmmakers, dubbed the “Hollywood Ten,” refused to hand over names of other suspected communists

and were sent to jail. When a group of liberals led by Humphrey Bogart flew to

Washington to protest the congressional hearings, they faced such a skewering

in the press that they immediately backed down. A blacklist was instituted.

Jack Warner went before the committee and boasted about firing a dozen

suspected communist sympathizers at his studios. The other studios rushed to

keep up.

For his part,

Ryan had always made his political views clear. To coincide with the release of

CROSSFIRE, he’d already published articles in The Daily Worker denouncing

anti-Semitism, and now that CROSSFIRE’s

director (Edward Dmytryk) and producer (Adrian Scott) were serving time for

refusing to testify before HUAC, Ryan appeared before the Jewish Labor Council,

a group the government considered to have communist affiliations. He gave a

speech at a “Keep America Free” rally

organized by the Progressive Citizens of America and told the audience, “We

protest the threat to personal liberty…represented by this police committee… We

demand, in the name of all Americans, that the House Committee on Un-American

Activities be abolished, while there still remains the freedom to abolish it.”

J.R. Jones

nicely answers a question that has long perplexed astute observers of film

noir. Namely, how did an outspoken liberal like Robert Ryan manage to keep from

being blacklisted during the worst days of the Red Scare? Over the course of THE LIVES OF ROBERT RYAN, Jones

identifies three main factors in saving Ryan’s career. One, he’d served in the military during the war,

something that many of his outspoken political opposites (like John Wayne)

couldn’t

claim. Two, he worked at RKO, which was run by Howard Hughes, and while Hughes

was a rabid anticommunist, he was also a man utterly controlled by his own

unfathomable whims. Hughes hung onto Robert Mitchum despite his notorious 1948

drug bust and Robert Ryan despite his lefty politics because, well,

he liked them. Besides, as Jones also points out, Hughes had so sliced and

diced the creative roster at RKO (while keeping a virtual harem of pretty

starlets on the payroll) that Mitchum and Ryan were practically the only bankable

male stars he had left.

The third

factor that saved Ryan’s career is that he was willing to do some

practical political maneuvering when the need arose. When Mitchum was serving a

brief period in lockup after his marijuana bust, it was Ryan who took the

starring role in Hughes’s litmus test project, I MARRIED A COMMUNIST (1949). A “redbaiter” that found Ryan duking it out with a gang of

wicked commies, the movie flopped at the box office.

“In

later years Ryan could barely bring himself to mention the picture,” Jones tells us, but while Ryan hated doing

Hughes’s

hammy propaganda piece, it helped save his job, and over the course of the late

1940s he managed to star in many of his best films. For director Fred Zinnemann

he played a vengeful ex-serviceman stalking a fellow soldier in 1948’s ACT

OF VIOLENCE (a film which remains one of the greatest noirs that most

people have never seen). For Max Ophüls, he played an insane misogynist millionaire

(in the image of you know who) in the excellent 1949 noir CAUGHT.

And for Robert

Wise, he made his greatest film, THE

SET-UP (1949). Ryan stars as Stoker Thompson, a past-his-prime boxer

heading into a bout with an up and coming fighter. The fight has been fixed,

but Stoker’s

managers don’t

tell him because they figure he can’t win anyway. Brilliantly staged and shot,

featuring the best fight sequence in classic film, THE SET-UP belongs in the upper echelon of noir films, and at

its center, believable and human and tragic, is Robert Ryan giving the

performance of his career.

He would give

other terrific performances — an obsessive cop in ON DANGEROUS GROUND (1951); a psycho in BEWARE MY LOVELY (1952); a millionaire double-crossed by his

evil wife in INFERNO (1953) — but Jones reveals that Ryan’s

focus in the early 1950s turned more and more to the school that he had founded

with Jessica. They launched the Oakwood School in 1951 as an integrated

progressive grade school, and Jones quotes Jessica as saying that they made up

their minds “to

call a spade a spade — meaning calling progressive progressive, even though the word had lately become suspect.”

Jessica would be the driving force of the school, serving as president of the

board and helping to write the curriculum. The Ryans sank their money and

passion into the school (which is still operating today), and they considered

its success their greatest professional accomplishment.

Throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s, Ryan stayed politically

active. He gave speeches for the ACLU, the NAACP, and the United World

Federalists. He co-founded the Hollywood chapter of the National Committee for

Sane Nuclear Policy. In 1959, he co-starred in ODDS AGAINST TOMORROW, which starred and was produced by Harry

Belafonte. It was one of Ryan’s finest films (and his last classic noir), and

he and Belafonte would become lifelong friends. Through Belafonte, he would

meet and become a supporter of Dr. Martin Luther King.

In the late 1960s,

Ryan had achieved the status of elder statesman in Hollywood, but he didn’t

rest on his laurels. He stayed relevant in films like THE PROFESSIONALS (1966), THE

DIRTY DOZEN (1967), and THE WILD

BUNCH (1969). In the early 1970s, filmmakers started tapping into his

classic noir persona, and he starred in neo-noirs like René Clment’s

David Goodis adaptation AND HOPE TO

DIE (1972) and John Flynn’s Richard Stark adaptation THE OUTFIT (1973). Appearing on Broadway,

he was a mentor to up-and-coming actors such as Stacy Keach and Jeff Bridges,

and his final triumph was on the stage, in a heralded production of THE ICEMAN COMETH (1973).

Jessica was

diagnosed with cancer in 1972 and died only ten days later. Ryan was

devastated, but he tried to carry on. He threw himself into working (and

drinking), but he would die just a little over a year later, in July of 1973.

Following his death, Pete Hamill would write a striking tribute to Ryan,

calling him “a

good man in a bad time.” By the time J.R. Jones closes out his masterful

biography of the actor, the reader can only agree.

Thursday, June 30, 2016

THE STUDENT NURSES (1970)

I've always felt that there was a kinship between the film noir of the 40s and 50s and the exploitation movies of the 60s and 70s. This is not to say that noir gave birth to exploitation--there were already exploitation movies in the 30s, 40s, and 50s, usually of the "hygiene movie" or "vice film" variety--that were the direct precursors of the 70s skin flicks. Still, in a lot of ways the low budget B-movie noir has a similar ethos to the exploitation movies that followed it. Both usually centered on crime, both trafficked in open appeals to sex and violence, and both were innately subversive.

The other night I got to see one of the real gems of 70s exploitation when the indispensable Chicago Film Society showed a rare print of Stephanie Rothman's THE STUDENT NURSES in their summer series. Produced by Roger Corman, the film follows four student nurses as they attempt to navigate various personal and professional crises on their way to graduation day. The film is famous today because of its unmistakable feminist and radical storylines. Here's a cheap would-be "sexy nurse" movie in which one of the heroines gets a still-illegal-at-the-time onscreen abortion while another gets involved with Mexican urban guerrillas. This is not just another skin flick.

I have to admit that I straight-up loved this movie. It's a wonderfully weird hybrid of subversive art and cheapie exploitation. Rothman was required to meet certain quotas of nudity and violence, but she does this paying-the-bills grunt work in interesting ways. The violence (all viscerally well done) mostly revolves around the urban guerrillas and is portrayed from their point of view, a stark contrast to mainstream cinema of the time, which largely used urban guerrillas as clay pigeons in cop movies. Here, when one of our heroines decides to use her medical knowledge to help her revolutionary friends, the choice is presented as being as legitimate as any other choice.

The director's handling of nudity is equally interesting. First, she includes as many naked male bodies as female bodies, which negates the typical imbalance in virtually all cinema in which men retain power positions as clothed (and hence in control) while women are naked (and hence exposed and vulnerable). This also means that everyone in the film is sexualized, not just the women. Secondly, Rothman finds interesting ways to incorporate the nudity into the story, including a LSD drug trip that is both a turning point in the plot and an important piece of character development. Another subplot in the story involves the relationship between one of the nurses and a patient. Given the fetish fixations of the sexy nurse subgenre of exploitation and porn, one would predict that this relationship will end in the nurse taking off her clothes, which, indeed, she does, but Rothman plays the scene for pathos rather than titillation. We know the patient is dying, and the scene is less about sex (they don't have sex, actually) and more about human connection.

I also should say a word about the abortion subplot, which is the element that makes the film the most transgressive to this day. Most films dealing with "unwed" mothers--including the crisis pregnancy noirs I wrote about in my piece "Women In Trouble" for Noir City--resulted in the death of the young woman, a de facto way of punishing her for her transgression. (The unwed fathers in these cases, it almost goes without saying, rarely died.) Not only does the young woman here live, but chooses to have an illegal abortion (after first being unable to secure a legal procedure). The abortion is shown here (not graphically), at a time when even mentioning abortion was extremely rare onscreen. Thus, this goofy exploitation movie is one of the first films to deal with abortion from a feminist perspective in a way that doesn't punish the young woman.

I won't make the claim that THE STUDENT NURSES is great art. It's got its share of wooden performances and budgetary shortcuts, clunky lines and awkward staging. What I will say, however, is that it's far closer to great art than it is to a real bottom-barrel tits-and-ass exploitation movie like 1969's THE BABYSITTER. It's an inventive, fun, subversive time capsule from a director who was given the materials to make a film with themes that were important to her, exploring perspectives never would have been allowed in the mainstream, perspectives that still rarely make it to the screen today.